Most people think food texture is fixed.

You cook something, it’s soft or it’s crunchy, and that’s that. But texture isn’t static. It’s alive. It changes with temperature, time, moisture loss, and even how a food was cooked in the first place.

If you’ve ever reheated leftovers and thought this isn’t the same food, you’ve already experienced this problem. If you’ve ever watched someone struggle more with a meal halfway through eating than at the start, this article is for you.

Because for some people, cooling food doesn’t just change enjoyment. It changes effort, and sometimes safety. And almost nobody talks about it.

Texture is Temperature Dependent

When food cools, several things happen at once:

- Fats solidify

- Starches reorganize

- Proteins tighten

- Moisture redistributes or evaporates

None of that is obvious while you’re eating, but your mouth notices immediately. That creamy mashed potato becomes pasty. That tender chicken becomes chewy. That soup develops a skin. That sauce thickens… then turns gluey. Lets take a closer look at the properties of the foods we eat that cause these changes and make a plan to address or avoid them all together.

Fats Firm Up

When food is hot, fat is doing useful work. Melted fat moves easily. It coats food evenly, fills in rough edges, and helps everything slide. That’s part of why hot food can feels smooth and easy to eat.

As it cools, that changes. Fats don’t all solidify at the same temperature. They start firming up gradually, and when they do, they stop acting like a lubricant and start acting like a coating.

You see this clearly with:

- Cheese, which stiffens and starts to cling instead of stretch

- Butter heavy sauces, which feel greasy rather than silky

- Fatty meats, which develop that unmistakable waxy feel

Once fat firms, it doesn’t help food move through the mouth anymore. It sticks to surfaces. Tongue, palate, teeth. Clearing each bite takes more work, even though the food itself hasn’t gotten “hard.” That extra effort adds up.

If saliva is limited, if someone eats slowly, or if they’re already working a bit harder to chew or swallow, cooled fat may become a drag instead of a benefit. That’s why foods that feel rich and luxurious when hot can feel heavy when warm and borderline unpleasant once they cool. The flavor hasn’t changed much, but the physics has. Fat stopped helping and started getting in the way.

Starches Get Thicker, Then Stiffer

Starches behave beautifully when they’re hot. Heat lets starch granules swell, soften, and loosen their grip on each other. That’s why hot mashed potatoes feel fluffy and why rice feels tender. As food cools, starches start reorganizing. The chains line back up, squeeze out water, and pull tighter.

At first, this tightening can be helpful. A stew thickens. A sauce gains body. Everything feels more cohesive. Then it keeps going.

Suddenly the food:

- Holds its shape instead of yielding

- Clings to the spoon instead of flowing

- Feels sticky or gluey in the mouth

That stickiness is the key issue. Sticky foods don’t break cleanly. They stretch, smear, and hang on, which means more chewing, more tongue work, and more effort to clear a bite.

Resistant Starches

As starches cool and realign, some of them become less digestible and more structured. Nutritionally, specifically for people whose body has difficulty managing blood sugar levels, that can be a benefit. Texturally, it often means food that’s firmer and denser in the mouth than it was when hot. The food became organized, and organized starch resists movement.

That’s why leftovers made from rice, potatoes, pasta, or thickened sauces often feel heavier and harder to manage, even when reheated. Once starch chains have tightened and set, reheating doesn’t fully undo the structure. That shift increases effort over time. It’s subtle, but it compounds. For someone who eats slowly, takes breaks, or needs food to stay predictable, starch behavior can quietly turn a comfortable meal into a tiring one.

Proteins Tighten and Dry Out

Protein fibers contract as they cool, especially if they were cooked hot and fast.

That’s why:

- Chicken breast tenses into a knot

- Fish flakes become rubbery

- Eggs firm up more than expected

Moisture gets squeezed out of the protein structure, leaving food that looks the same but behaves very differently in the mouth.

Moisture Moves (and Not Always Where You Want It)

Cooling doesn’t just dry food out. Sometimes it does the opposite. Moisture can migrate to the surface, creating:

- Watery puddles under solid foods

- Slimy coatings

- Skin formation on soups and purees

So now you have mixed textures in one bite. A firm center with a slick exterior. A soft food swimming in thin liquid. That inconsistency is hard for anyone to manage, even without swallowing challenges.

Why This Matters Beyond “Picky Eating”

Most people blame themselves when food suddenly feels harder to eat. They assume:

- They’re just tired

- They don’t like leftovers

- They’re being fussy

But in reality, the food changed.

Texture shifts increase:

- Chewing time

- Mouth/jaw/tongue fatigue

- Residue left behind after swallowing

If someone already has reduced strength, coordination, or sensation, cooling food can quietly push a meal from manageable to overwhelming. This is why people often eat less as food cools. Not because they’re full. Because the effort creeps up bite by bite.

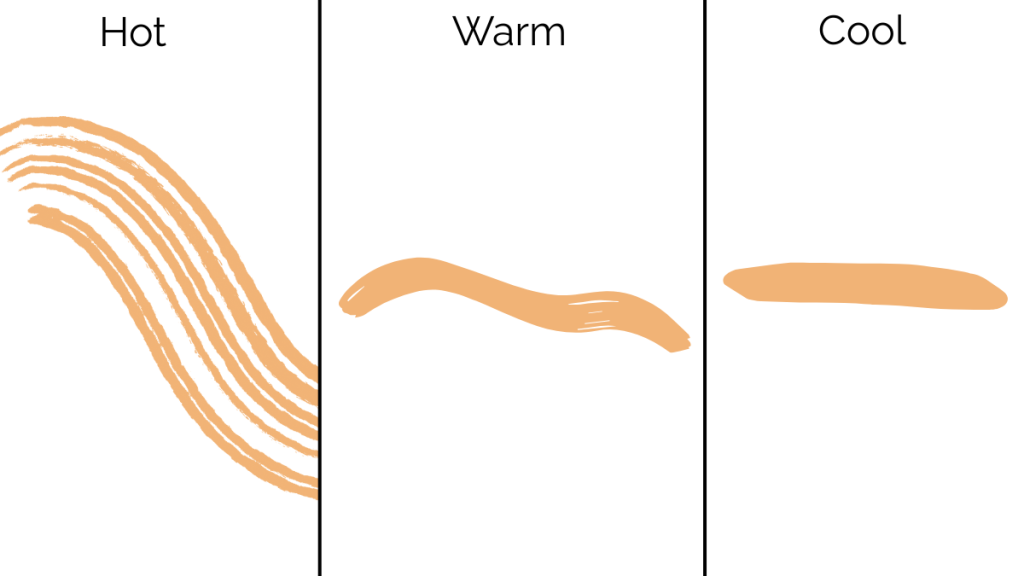

The Overlooked Role of Time During a Meal

Most meals aren’t eaten piping hot from start to finish. Plates sit, food rests, conversation happens. By the time someone reaches the last third of a meal, the texture profile can be completely different than the first few bites. The safest bites happen early and the hardest bites happen at the end. If someone routinely leaves food unfinished, texture drift may be the real culprit.

Culinary Techniques That Make Foods More Forgiving as They Cool

his is where cooking knowledge becomes powerful. Some foods are naturally more temperature-stable than others. But technique matters just as much as ingredients.

Add Moisture That Stays Put

- Use emulsified sauces, which break fats into small droplets and suspends them in water, instead of plain fats

- Incorporate finely blended vegetables into dishes for fiber + hydration

These help maintain cohesion instead of separating as food cools.

Favor Gentle Proteins

Slow cooked, collagen rich cuts behave better over time than lean, fast cooked ones. Think:

- Braised meats

- Stewed legumes

- Gently poached fish

These stay tender longer and don’t tighten aggressively as they cool.

Control Starch Behavior

Starches don’t all cool the same way.

- Potatoes with added fat stay softer

- Rice with adequate moisture resists hardening

- Sauces stabilized with more than just flour behave better

Sometimes the fix isn’t less starch. It’s better supported starch.

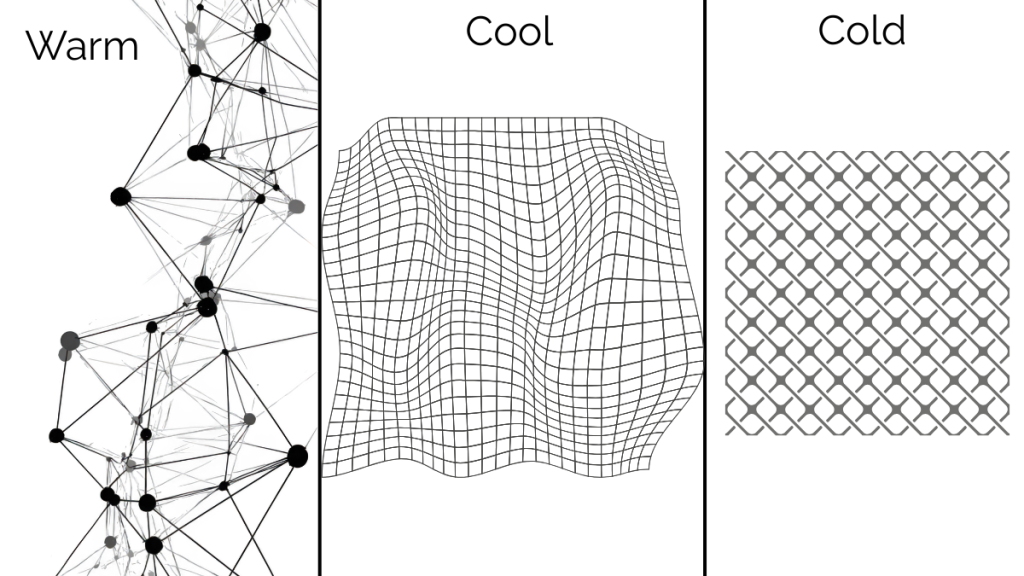

Build Texture That Degrades Gracefully

The goal isn’t just “soft.” It’s predictable.

Foods that change slowly are easier to manage than foods that flip suddenly from soft to sticky or tender to tough.

When Texture Changes Become a Safety Issue

For people with swallowing challenges, texture changes aren’t just inconvenient.

They can increase:

- Choking risk

- Aspiration risk

- Fatigue mid-meal

- Anxiety around eating

This is where structured texture guidelines exist, but you don’t need to know any of that terminology to understand the core idea: Food should remain manageable from the first bite to the last.

If it doesn’t, something needs to change.

What to Watch for at Home

If you’re cooking for yourself or someone else, these are quiet red flags that cooling texture may be the issue:

- Meals are abandoned halfway through

- Foods are pushed around but not eaten

- More coughing happens later in the meal

- “It was fine at first” comes up a lot

None of those mean failure. They mean information.

Texture Isn’t Just a Preference. It’s a Moving Target.

With recipes, we talk endlessly about flavor. But texture decides whether food is enjoyable, tolerable, or exhausting. And temperature is one of the biggest drivers of texture change that nobody teaches us to think about. Once you notice it, you can’t unsee it.

And once you start cooking with cooling in mind, meals get easier. More consistent. More satisfying. That’s the real goal. Not perfect food, not clinical perfection. Just food that stays kind to the person eating it.

Keep Reading

If you are new to noticing challenges with eating and drinking, check out my article about foods that take less effort to eat, or learn more about why “soft food” doesn’t always mean safe.

Every recipe here is SLP designed for texture sensitive eaters: from dysphagia to dental issues to picky eaters. Get recipe roundups and practical tips by joining the mailing list.

Leave a Reply